The tendency to compare your situation with those around you is ingrained in the human condition. Whether consciously or unconsciously, to some extent we all filter our decisions through a comparative lens.

Some are more burdened by these pressures than others but few of us operate unaffected by external opinion. Mark Twain put it like this: “outside influences are always pouring in upon us and we are always obeying their orders and accepting their verdicts”.

Consider your own situation: the house you live in, the car you drive, the clothes you wear. To what extent were these purchasing decisions driven by factors outside simple utility? A Toyota Vitz is more than capable of successfully executing the school run, yet few of these economical steeds are to be seen in the pickup zones around Auckland’s more salubrious schools.

At the risk of appearing holier-than-thou, it is worthwhile pointing out that I have just purchased a high-end, dual-suspension electric mountain bike capable of ascending Kilimanjaro for the sole purpose of completing my daily commute from Grey Lynn to Ponsonby, approximately three kilometres.

Lifestyle burn

Sociologists refer to the practice of buying and using goods of a higher quality, price or in greater number than practical as ‘conspicuous consumption’. Thorstein Veblen coined the term to explain the spending of money on luxury commodities and goods, specifically as a public display of the economic power, income and accumulated wealth of the buyer.

More colloquially, most of us know this as ‘keeping up with the Joneses’, an idiom derived from a popular cartoon strip that graced the pages of a number of American newspapers between 1913 and 1940. The strip depicts the McGinnis family who, as hard as they try, can never quite measure up to their always-slightly-more-impressive neighbours, the Joneses.

Upon self-reflection, you may not attribute your personal expenditure to these behavioural tendencies and perhaps feel your spending over the years has simply increased in line with your income/drawings.

In any case, the impact of an ever-increasing lifestyle burn, otherwise known as ‘lifestyle creep’, can have a significant unintended effect on your ability to materialise the things that are genuinely important to you over the long-term. This is the central point to this piece and one that I would like to demonstrate by way of hypothetical example.

Meet ‘Lucy’

In this instance, I will use Lucy, a fictitious newly-minted partner at one of Auckland’s top-tier firms, to demonstrate my point. Lucy is 40, has five-year-old twin boys, has just paid off her family home and spends around $200k per annum on lifestyle costs. She has just received her partnership letter and is considering the implications of her growing expected future income. She earned $550k in the last financial year and has been informed that this will increase steadily over her seven-year lockstep, settling at $900k per annum at full equity.

Lucy has four simple, but important, objectives:

- she would like to upgrade her family home when she turns 50, spending $1 million on an extension;

- she would like to retire when she turns 60;

- she would like to provide house deposits for her children, $300k per child when they turn 25; and

- she would like to leave a meaningful legacy, in addition to the family home, when she dies. Ideally this would be $1m-plus per child.

This scenario, albeit simplified, is one I come across regularly: an individual or family with a clear set of objectives, hoping to develop confidence that their desired future outcomes are realistic and achievable. So, is Lucy well positioned to achieve her goals?

To determine this, I will use financial modelling (a Monte Carlo simulation, to be specific) to forecast a probable range of outcomes based on a bespoke set of inputs.

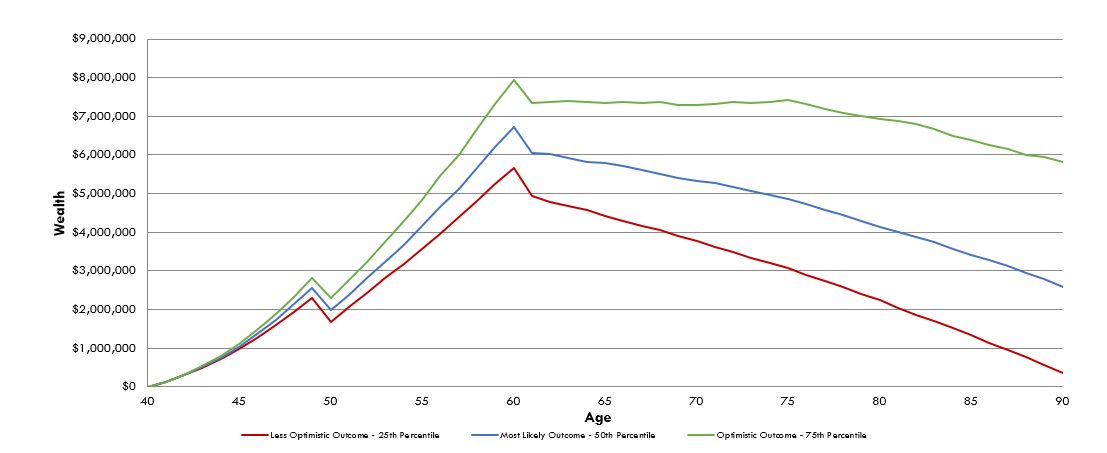

The charts (next page) show the expected growth of Lucy’s investment portfolio over time, assuming she invests her excess income (net income minus expenses) throughout her earning years.

Executed well, this is an extremely powerful tool that enables you to approach financial decision-making strategically, incorporating your financial objectives and minimising the chance that any particular decision derails your overall financial plan.

In Lucy’s case, assuming she can maintain her $200k per annum lifestyle, things are looking good. Her portfolio, assuming conservative growth expectations, is likely to be able to sustain a $1m withdrawal at age 50 and a house deposit withdrawal at 61 when the kids turn 25.

On retirement at 60, when Lucy starts taking distributions from her portfolio to fund her lifestyle costs, we see a downward slope showing her portfolio slowly diminishing. The modelling suggests this rate of spending is sustainable as all three probability ranges, less optimistic (red), expected (blue) and optimistic (green), show that at 90 there will be cash left in the pot.

Importantly, the most likely outcome (blue) suggests around $2.7m will be left over, leaving ample capital to achieve Lucy’s objective of leaving her kids a meaningful legacy.

With this baseline established, let’s now look at a different scenario, one where Lucy’s annual spend ratchets up over the first few years of her partnership to ‘keep up with the Joneses’.

Unintended implications

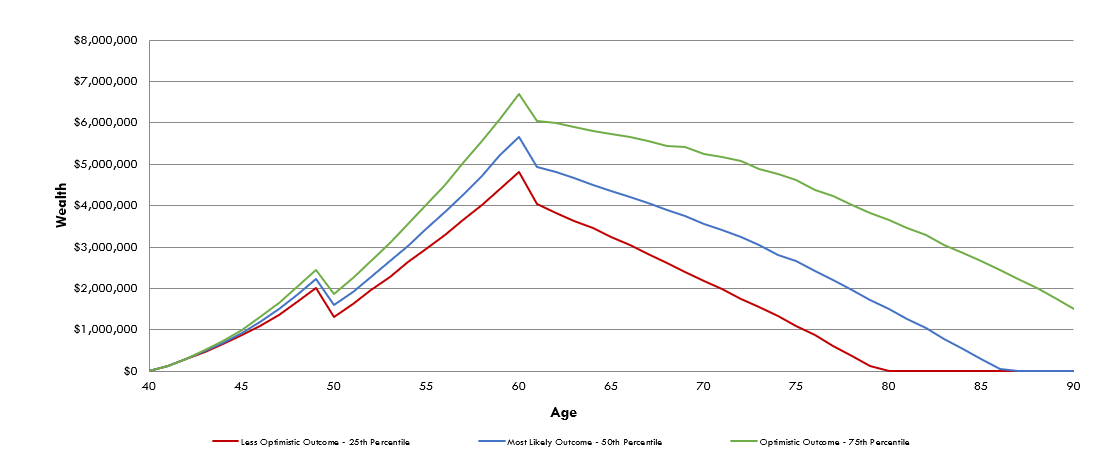

Let’s assume that throughout the first five years of her lockstep, she increases her lifestyle spend by $10k each year, settling at $250k per annum. Relative to her increasing earning power, this modest increase would likely feel reasonable. However, as alluded to earlier, the impact of unchecked increasing expenditure can have significant unintended implications for long-term outcomes.

Remodelled with this new expenditure assumption, Lucy’s new scenario, below, now shows she is likely to run out of capital in retirement and the chances of providing a legacy to her children have diminished significantly.

Not ideal.

In this scenario, the prudent approach is to revisit Lucy’s objectives and make adjustments based on priority. One lever that could be pulled is to adjust Lucy’s planned retirement age from 60 to 65. This facilitates a further five years of investment contributions and as you can see in the chart below, it brings the long-term projected outcomes back into a comfortable probability range.

While this pivot has solved the retirement savings gap, it has come at the cost of retirement age. So, was the additional annual expenditure worth the sacrifice? Would a little less conspicuous consumption have made any difference to Lucy’s wellbeing?

In my experience, lawyers often neglect their financial affairs and end up accepting outcomes rather than creating them. I have a unique vantage on this as I have, for many years, been creating bespoke financial plans for legal professionals. Some, like Lucy, have been entering partnerships while others are planning their exit to retirement or, as is often the case, the Bar.

Ultimately, the decisions you make and the goals you prioritise are for you and your family to decide. The protagonist in this article was fictitious and, as such, this should not be viewed as personalised advice. But I hope the example demonstrates how thinking strategically about your own situation and developing a bespoke financial plan can help create better outcomes and limit undesirable trade-offs.

Rutherford Rede

91 College Hill, Ponsonby

Auckland, 1011, New Zealand

Rutherford Rede © 2023. All rights reserved.